HeyAlma dot com

Some Jewish activists are household names: Larry Kramer for his relentless work during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Betty Friedan for her vision of gender equality, Ruth Bader Ginsburg for her work on the United States Supreme Court. Even if these figures were at times controversial or imperfect, they spent their lives committed to their beliefs, and have rightly entered the canon of Jewish figures we admire.

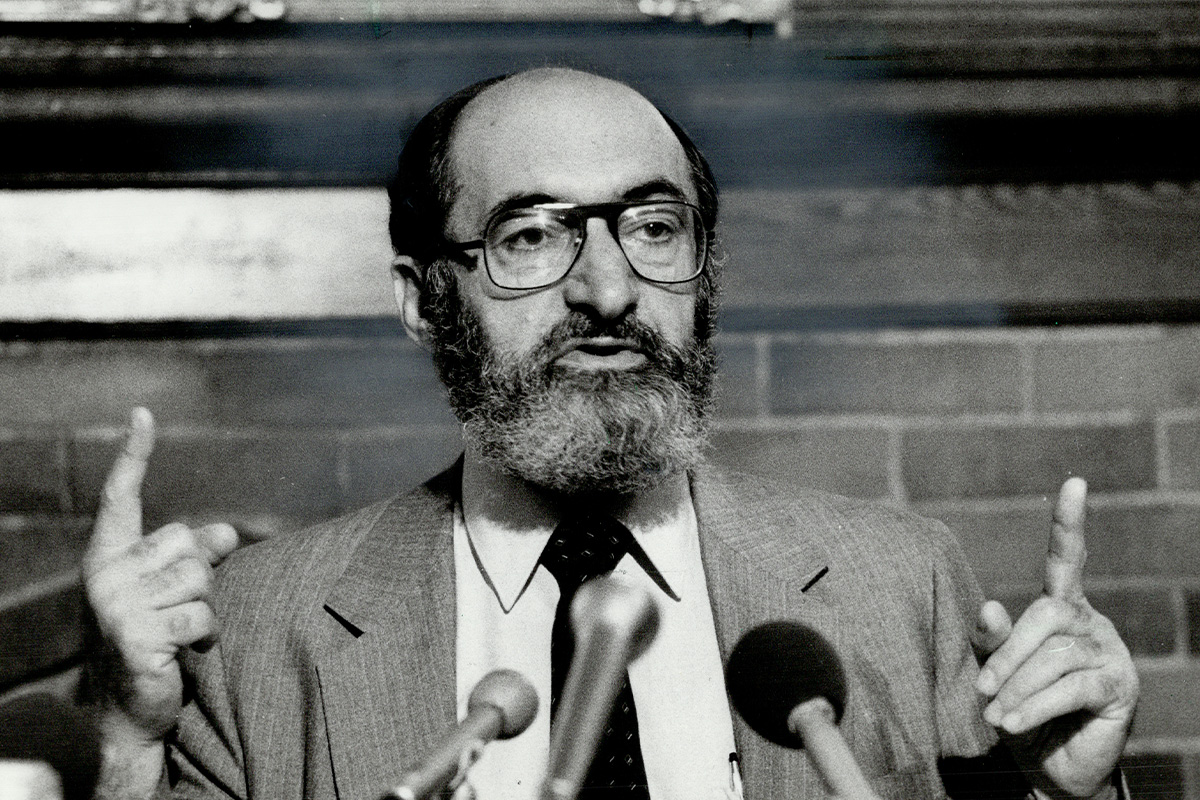

But for every Notorious R.B.G. bobblehead, there are countless other Jewish activists whose stories go untold. The late reproductive rights activist Dr. Henry Morgentaler is one such example.

Dr. Henry Morgentaler was born in Łódź, Poland in 1923, to two Jewish socialist parents. After the Nazis invaded Poland, his parents and older sister were imprisoned and later murdered in the Dachau concentration camp. Morgentaler and his brother were the sole survivors of his family.

Morgentaler eventually immigrated to Canada with his first wife, the poet and fellow Holocaust survivor Chava Rosenfarb. In 1950, he graduated from medical school at the Université de Montreal. In 1955, Morgentaler opened his own practice in a working-class neighbourhood in east Montreal, specializing in family planning and vasectomies.

It was through this work as a physician that Henry Morgentaler would soon find himself at the very center of Canada’s shifting abortion debates. It was also how he came to take the law into his own hands, pursuing justice through civil disobedience.

In 1967, Morgentaler presented a now-famous brief in front of the House of Commons in Canada, where he argued that Canada’s outright ban on abortions was an immoral act that endangered the lives of thousands of women each year. Two years later, Canada ratified the Omnibus Bill, which allowed for abortions so long as a panel of doctors deemed a pregnant person’s life to be sufficiently endangered.

While this ratification was a step forward for abortion rights, it was not the revolution many feminists were hoping for. Morgentaler critiqued the state-sanctioned committees for being too selective about what qualified as a danger to a woman’s life, and for being comprised almost exclusively of men. Seeing no legal recourse for women in need, he decided to start his own illegal abortion clinic in Montreal. His patients were mostly young women who otherwise would have sought dangerous abortions on the underground market, and sought him out for services they could not find safely elsewhere. By 1973, he had performed over 5, 000 clandestine abortions.

The consequences were severe. Morgentaler’s clinic was firebombed on multiple occasions, and he even resorted to installing bulletproof windows in his family home as a security measure. Antisemitic conspiracy theories proliferated throughout Canada, claiming that Morgentaler was targeting white, non-Jewish women in his abortions, and trying to bring an end to the white race. In 1970, soon after the clinic opened, he was arrested in a public raid (though he was quickly released on bail and continued practicing), and then arrested again in 1973.

Morgentaler’s trials following his arrest proved that public opinion was clearly on his side: The jury acquitted him of criminal charges not once, not twice, but on three separate occasions. This did not, however, save him from prison time. In 1973, after the first jury deemed him not guilty of violating the Criminal Code, the Quebec court overrode the decision and sentenced him to a year in prison anyways. This was a harsh year for the Holocaust survivor. He spent time in solitary confinement, and he paid nearly $300,000 altogether in legal fees from the ordeal.

Despite these challenges, Morgentaler emerged from prison still fiercely committed to a woman’s right to choose. In 1983, he established additional abortion clinics in Toronto and Winnipeg, and he continued practicing as a doctor until his retirement in 2006.

After surviving a genocide and the murder of his family, one might expect Morgentaler to relish any sliver of comfort that the remainder of his life could still offer. On the contrary, Morgentaler devoted nearly his entire adult life to a dangerous, contentious battle against injustice. He stood up for his principles with pride and dignity, even if it was not an issue that affected him personally. This is perhaps the aspect of Morgentaler’s legacy I admire most, and it is the part of his legacy I believe makes his story so mind-boggling; this ability to empathize with the struggle of other people persists even after enduring so much pain and suffering himself.

When the Supreme Court of Canada officially decriminalized abortion in 1998, the change was rightly credited to Morgentaler’s decades of activism. The Morgentaler Clinic still exists today and operates in cities across Canada.

Even more impressive, a year after the Quebec Court of Appeal overturned the jury’s decision and imprisoned Morgentaler, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau implemented a new law that dictated that a court did not have the right to overturn a jury’s acquittal, dubbed ‘The Morgentaler Amendment.’

Therefore, Morgentaler not only provided abortion access for thousands of Canadians, but his disobedience ultimately improved the basic conditions of democracy in Canadian courts.

Morgentaler still had flaws, of course, and I would be dishonest to write only of his positive qualities. He believed, controversially, that evil people were a consequence of children being born into families who were unable to provide sufficient love and care. Morgentaler thus saw abortion as a means to prevent future perpetrators of abuse from being born into the world, which is a view that is both unpopular and rooted in a deeply problematic social history.

Nevertheless, in an era in which American women and trans folks have lost some of their most basic freedoms, just north of the border, Morgentaler’s life of civil disobedience can inspire us to remember what fighting for Tikkun Olam looks like in practice. While Morgentaler might be remembered today as someone who emerged victorious and changed Canada’s legal system for the better, we must also remember the incredible sacrifices he made to achieve his goals, and that the path to progress was never easy.

Growing up in a sheltered suburban home, it never crossed my mind that a woman’s right to choose could be anything but settled law. I admit this is a consequence of male privilege and ignorance bout how deeply patriarchy runs in our society. However, recent news in the U.S. shows how quickly decades of progress can unravel. The same could happen here in Canada, too. Although it is decriminalized, the Canadian courts never codified a law safeguarding abortion rights, either. We cannot become complacent and take legal victories for granted anywhere in the world. There is no other option but solidarity.

Morgentaler’s journey is an important reminder that challenging an unjust law is a slow, long march that often takes years to render real results. He spoke up about a law that endangered the lives and liberty of Canadian women, often to the detriment of his own comfort and safety. His legacy reminds us all that laws in a liberal democracy should be designed to benefit the people, not just the interests of an unelected court. A survivor, a man of the people, and a stalwart pro-choice feminist, Dr. Henry Morgentaler deserves a slot on your Jewish-American history syllabus. While his activism started in Canada, his legacy should resonate across the world.