President-elect would prefer to sideline it in order to focus instead on Iran nuclear deal re-entry

ed note–not that it will get as much as a cat’s whisker of notice, including on the part of a whole bunch-a EKSPURTS who think they have this whole ‘Jooish’ thing figured out, but this piece within just the 9 words making up its title explains the entire ‘Get Trump’ operation on the part of Judea, Inc from the earliest days of when he was just ‘candidate’ Trump.

It is/has been this, DJT’s plans for a ‘peace deal’, coupled with his refusal to engage in any more ‘endless wars’ for Israel that explains why there has been a seek-and-destroy mission on the part of the pirates of Judea out to stop him from building a cage around the monster and in quarantining the Judaic virus.

As far as Biden revisiting the ‘Iran Deal’ otherwise known as the JCPOA, keep in mind that Netanyahu is not as opposed to this as his pretenses and performances suggest. The JCPOA was created FOR THE PURPOSE of setting Iran up for destruction despite what appears to be a surrender of America and the West to Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

Please note the sections in red, and particularly those quoting Tamara Cofman Wittes, a ‘nice Jewish girl’ as she likes to call herself, who is plugged into every major Zionist organization within America’s foreign policy think tank neighborhood.

Times of Israel

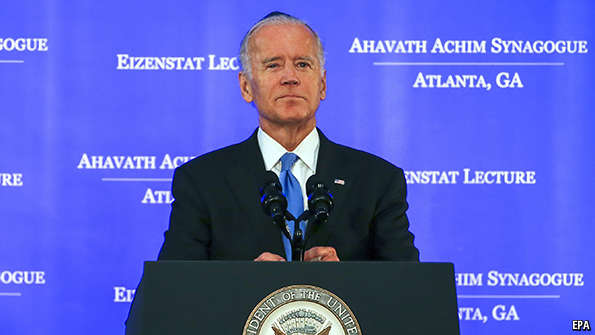

Unlike his predecessors, US President-elect Joe Biden is not entering office with plans to launch a major Israeli-Palestinian peace initiative.

There’s no talk of reaching the “ultimate deal,” as Donald Trump described it in 2016, and there’s no intention of appointing a special envoy for the Middle East on his first day in office as Barack Obama did in 2009. No marathon peace negotiations like the ones led by Obama’s secretary of state John Kerry in 2013 and 2014 and no Vision for Peace like the one unveiled by Trump and his son-in-law/adviser Jared Kushner in 2019 and 2020.

“This isn’t 2009, it’s not 2014 and it’s not 2017. The parties are far from a place where they’re ready to engage on negotiations or final status talks,” Biden’s nominee for secretary of state Tony Blinken told The Times of Israel days before the presidential election.

Blinken clarified that the incoming administration wouldn’t forgo the issue altogether, “because ignoring Israel-Palestine won’t make it go away.”

But when shielded by assurances of anonymity, some Biden aides have been more willing to admit that Israel, and even the Middle East more broadly, is not going to receive the amount of attention that it has enjoyed during the tenures of recent presidents.

One senior adviser to the campaign told Foreign Policy magazine in October that the Middle East would be “a distant fourth” in the list of foreign policy priorities, after Europe, the Indo-Pacific, and Latin America.

Another foreign policy adviser told The Times of Israel before the election: “It’s not that a Biden administration won’t focus on Israel. It just might not be given center stage like it has been in recent years.”

The conflict will almost certainly be overshadowed by other issues in the region, namely the Iran nuclear deal, which Biden has made clear he plans to rejoin if Tehran agrees to return to compliance with the multilateral accord.

Intentions are all fine and good, but whether the reality on the ground between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea can cooperate is another question.

Several regional analysts who spoke with The Times of Israel argued that if Biden is hoping to put the Israeli-Palestinian conflict aside to focus on other crises at home and abroad, he could have another thing coming for him. However, they acknowledged that there is a middle ground that can be struck in which the issue doesn’t receive the attention to which its been accustomed, but is managed in a way where a foundation for future talks can be built for when the sides are ready to reengage.

‘Not engaging is engaging’

Of course, there’s good reason for Biden’s desire to avoid over-focusing on the Middle East, let alone the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“For the president-elect and his team, they’re coming into office at a moment of national crisis with profound domestic impact in terms of public health and economics that is urgent and happening right now. So that’s priority one, two and three. It just has to be,” said Tamara Cofman Wittes, who served as deputy assistant secretary for near eastern affairs during the Obama administration and is now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute in Washington.

“When you’re looking at foreign policy as a whole or the Middle East as a region, there are, yes, lots of items on the agenda as well as lots of demands from America’s international partners for engagement,” she said, arguing that the Trump administration had left allies in the dark about policies impacting them.

In the Middle East, Iran will enjoy more attention given that Tehran’s nuclear pursuits are seen as a more pressing issue for Biden, explained Martin Indyk, who served as US special envoy during the Kerry peace talks and is currently a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

Indyk said Biden is very familiar with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, “intimately aware” of the peace negotiations he helped lead, and understands “the difficulty” of reaching a final status agreement between Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas.

“As long as Netanyahu leads Israel and Abbas leads the PA, the chances that the gap between them could somehow close aren’t very likely, and I think that is the view of President-elect Biden,” Indyk said.

But Lara Friedman, an ex-US foreign service officer in Jerusalem and current president of The Foundation for Middle East Peace in DC pointed out that Biden would not be the first president to say he’d tackle the issue when he’s good and ready. “If you don’t want to come for Israel-Palestine on your own terms, it’ll make you come on its terms. So pick one,” she said.

“In 2021, it is not as if there is a stable status quo there,” she said, highlighting Israeli settlement building on more and more West Bank land that the Palestinians hope will one day be included in their state.

“Not engaging is engaging, and not engaging is engaging in support of the status quo forces,” Friedman argued.

Don’t get burned

Indyk assured that Biden recognizes that avoiding the issue altogether would ultimately “come back and bite the administration in some way.”

“The most obvious way for this to occur is through settlement activity,” argued Indyk, a heavy critic of Israeli construction in the West Bank.

He pointed to the recent advancement of a project in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Givat Hamatos, which would effectively cut Palestinian parts of the capital from the southern West Bank city of Bethlehem.

The final day to submit construction bids for the plan is January 18 — two days before Biden enters office. Indyk speculated that a further advancement of the Givat Hamatos project would lead to the issue being raised in the UN Security Council, forcing the Biden administration to take a position on the matter.

Indyk pointed out that Obama’s famous 2016 abstention at the Security Council on a resolution condemning settlements allowed for the establishment of an “automatic mechanism” for the top body’s engagement on the issue. The UN’s special envoy to the Middle East Nikolay Mladenov has since been required to provide quarterly updates to the Security Council on settlement construction, keeping the issue at the top of the forum’s agenda.

The Trump administration’s stance against criticizing settlement construction has ensured that no further such resolutions have passed. Indyk speculated that with Trump out of office, other countries on the Security Council might be emboldened to submit additional resolutions against Israel, including ones calling for international sanctions against the Jewish state.

“Biden will have to take a stance at a time when he’s trying to advance multilateral diplomacy and does not want to be issuing vetos in the Security Council, especially on an issue he’s opposed to,” said the former Obama envoy.

For her part, Wittes downplayed the argument that the US and Israel cannot reach an agreement for some sort of limitation to settlement construction. She pointed to the 10-month freeze instituted by Netanyahu in 2009 at Obama’s behest, which was part of a US effort to jump-start negotiations. Ultimately, the period expired before Abbas agreed to come to the table. “None of that is a narrative of a major US-Israeli clash,” Wittes argued.

“Settlements are an issue on which the US and Israel have managed to have constructive engagement for a long time and I refuse to accept the idea that it’s impossible to… make progress on that,” she added.

But another way the conflict could intrude on Biden’s agenda, Indyk said, would be a decision by the International Criminal Court’s pre-trial chamber deeming that The Hague has jurisdiction to open a criminal probe into possible war crimes committed by Palestinians and Israelis in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem.

An already overdue ruling at the ICC is expected in the coming months and Indyk argued that a decision to probe Israel would “lead Prime Minister Netanyahu to come knocking on Biden’s door begging for help.”

Another issue that could bring the conflict onto Biden’s agenda is the effort to broker additional normalization deals between Arab countries and the Jewish state.

Blinken said a Biden-Harris administration would support such developments; and Indyk speculated that possible candidates such as Saudi Arabia would take a similar strategy to the one employed by the United Arab Emirates — which tied normalization to the Palestinian issue by conditioning the agreement on Israel shelving its West Bank annexation plans.

But possibly the easiest manner in which the Israeli-Palestinian conflict could skip to the top of Biden’s agenda would be if violence breaks out in the West Bank or Gaza. The territories have been relatively quiet in recent months, but are not known for extended periods of calm. Such escalations have required the intervention of US administrations in the past.

In addition to prejudicial developments that could force Biden to act, a series of positive steps could also beckon the president’s engagement.

Friedman pointed to the recent decisions by the PA to resume security cooperation with Israel and to once again accept tax revenues from the Jewish state — both domestically unpopular moves. These measures are reportedly being followed by efforts in Ramallah to move away from its payments to Palestinian security prisoners.

“These are all really loud statements by the Palestinians saying ‘We’re ready to be constructive partners,’” Friedman argued.

“A Biden administration that doesn’t take advantage of these openings would be sending a pretty clear message that they’re never going to engage on the issue,” she said. “Because those are the kinds of things that people who say the Palestinians are not partners for peace point to, arguing that ‘If they were partners they’d do X, Y and Z.’ Well they’re doing X, Y and Z. Now what?”

Avoiding the ‘whole enchilada’

For her part, Wittes argues that engagement on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict need not be a zero-sum game.

“There are lots of ways to pay attention to this conflict and to try and improve the situation other than appointing George Mitchell special envoy on the first day,” she joked, referring to Obama’s one-time envoy.

“You can start from where the conflict is… recognizing that it is not currently ripe for resolution,” Wittes said.

From there, the US can move to “repair and improve its own capacity to be an effective convener and mediator. That means at a minimum reestablishing a diplomatic channel with the Palestinians,” she said, while asserting that doing so does not require a distancing from Israel.

Wittes added this would also necessitate resuming coordination of policies regarding the conflict with other international and regional actors who have a stake in the matter.

“Trump did not consult European partners who make up a large portion of the PA budget. He didn’t engage at the UN even though the UN is a major player through Nikolay Mladenov. He basically slammed the door on the Jordanians who… have helped to defuse a number of crises in the past. Resuming that kind of policy coordination with the parties of the conflict is critical,” she said.

The Brookings scholar went on to argue that Biden could also address some of the more urgent issues on the ground that create tensions between the parties. “Whether it’s the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, the way the COVID crisis cannot be solved by either side on its own… These are urgent issues that demand attention just to keep things from getting worse.”

The third recommendation Wittes offered for tempered engagement on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was to “prepare a new foundation for effective negotiations down the road.”

She pointed to public opinion data showing that both Israelis and Palestinians still prefer a two-state solution, while also believing that it’s not possible, and that the other side cannot be trusted to uphold such an agreement.

“So you’ve got to rebuild that faith,” Wittes said, pointing to the recent normalization agreement as a place to start. “You can see the impact that those agreements are already having on Israelis, and that’s very hopeful. So I don’t think it’s impossible to rebuild that sense of possibility.”

“I don’t think that all of that work requires the day to day attention of the president,” said Wittes. “I do think it requires the president wanting that work to get done.”