ed note–once again, the typically Judaic practice of refusing to come to grips with reality, and especially that reality that surrounds Judaism, its adherents and the unavoidable/crushing weight of history as pertains this aberrant ideology and its acolytes.

The Forward

There is much to love about Hanukkah: the beauty of dancing flames on winter nights, the taste of crisp latkes, singing with friends and family, and the promise of everyday miracles in the most hopeless moments. Sufganyiot even play a role in my courtship story with my husband, forever tingeing the holiday with a dose of deep-fried romance.

But now that I have two school-aged stepchildren, I am increasingly noticing how out-of-date the 1980s version of the holiday that I grew up with is. Hanukkah is in desperate need of a 21st Century makeover.

Next to healthy dollops of applesauce, we were raised on heaping servings of a cartoonish Hanukkah account pitting good against evil. On one side: brawny, swash-buckling, underdog Maccabees defending Judaism to the death. On the other side: the evil King Antiochus quashing Jewish self-expression.

As with every lesson from my day-school days, the Hanukkah story is exceedingly more nuanced, revealing that far from speaking for the Jewish populace on the whole, the Maccabees were in fact religious zealots who enforced their perspectives on the more assimilated, Hellenized Jews of the time with tactics including forced conversion, forced circumcision and murder.

While I’m not advocating that we teach six-year olds about Jewish civil war circa 164 BCE, isn’t it time that we back off the hero narrative of rather dubious heroes? Even for those not ready to accept the complexity of the motivations of Mattathias and his gang, the militant thrust of the way in which we continue to tell the story to our children seems highly ill-fitting for today’s family, and especially in an era of devastating public violence.

Ennobling bearded, muscly men with swords and shields is so passé yet lingers in the holiday paraphernalia we mindlessly distribute to the next generation of Jews. Amidst a Hanukkah display at a downtown Toronto supermarket, alongside candles and dreidels, I spotted a package of foil-wrapped chocolate Maccabees suited up with swords and shields. Even at the progressive Jewish afterschool program that my kids attend, a class collaborated on a larger than life-sized portrait of Judah grinning as he heads off to battle. What are children gaining? How does making art of ancient Jewish militiamen bolster their Jewish self-understanding?

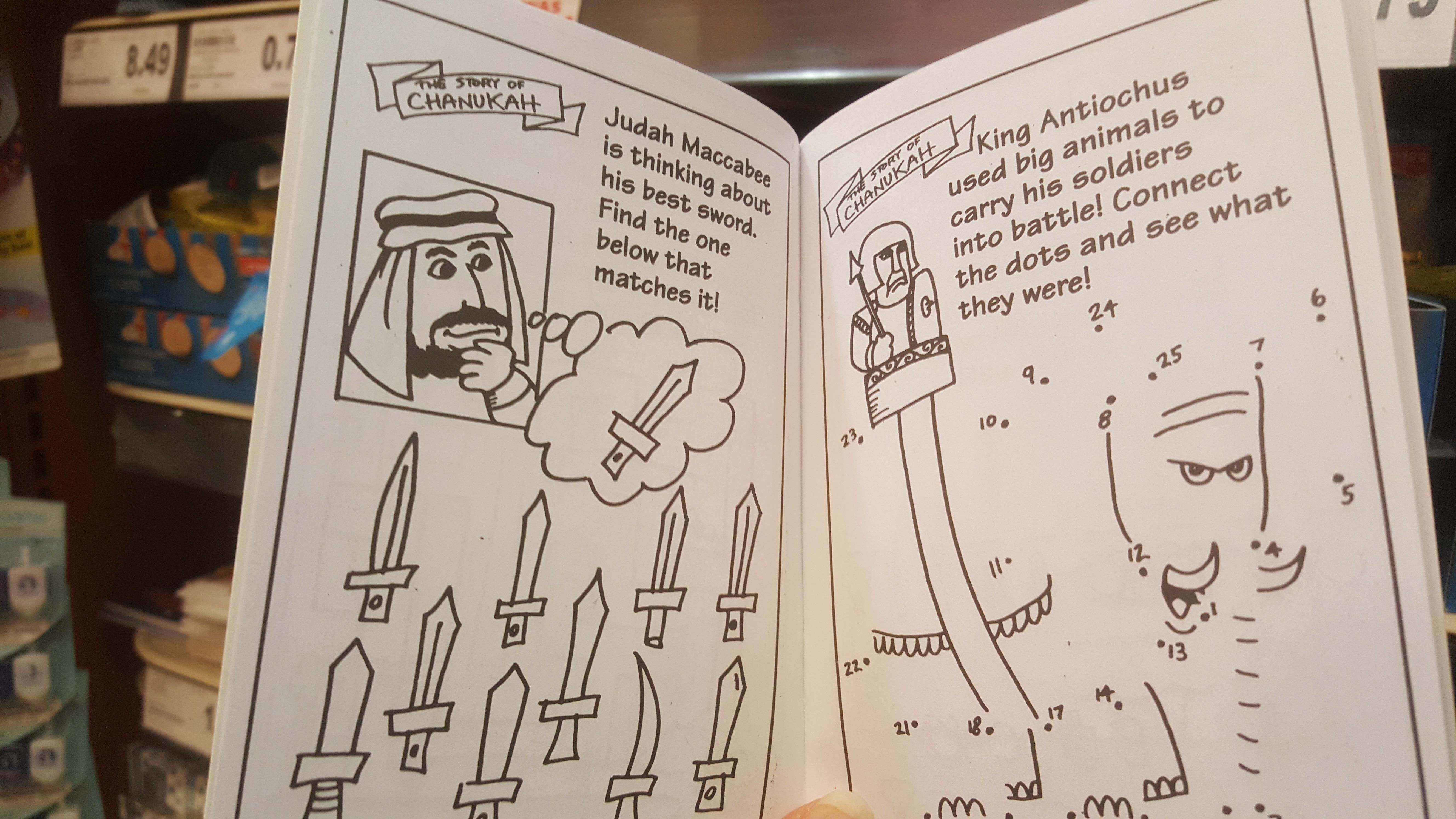

In the same supermarket display, I picked up a booklet billed as a “delightful and educational activity book [that] teaches children about one of their favorite holidays.” The first page opens to the declaration: “King Antiochus was a wicked king who once ruled the land of Israel” with said ruler ironically depicted as hook-nosed and grimacing menacingly with pointy teeth. Even without the infusion of more historical complexity about the Hellenist ruler known as Antiochus, it is time to position our festivals in a more positive light rather than persisting with an elemental story of bad guys out to get us. I am always amazed at the ease with which Jewish discourse paints entire peoples with one brush as “evil” and “wicked” when we know all too well the consequences of mass stereotyping, of spreading notions of an entire people as debased and worthy of extermination. Can we not offer our children a version of the holiday that is more relatable, less violent and less dominated by bearded men and evil enemies?

Lately, I have noticed signs everywhere that the simplified stories of our youth persist even as we grow into theoretically more sophisticated adults. A Toronto-based organization that aims to “bring the next gen of Jews together to become closer to one another and their roots with depth, meaning, and a lot more love,” is hosting a Combat Archery Hanukkah event for Jewish young adults dubbed “Capture the Oil.” Their marketing materials promise to pit Jews against Greeks. The latter are described as “seeking to send the world deeper into a dark void in the name of science, progress, and intellectuality.” This event is almost beyond belief. In 2017, a Canadian Jewish organization is promoting Greeks as our enemy while holding up science and intellectuality as debased and counter to the “righteousness of the Jewish people”? So much for programming with “a lot more love.” This misguided event, promoting combat and perpetuating a simple ‘us versus them’ narrative, highlights another hallmark of Hanukkah that requires an immediate overhaul: demonizing Greek people. If we feel compelled to teach our children some specifics of the Hanukkah story, we need to refer to them as Ancient Greeks and make the point that these events happened thousands of years ago. My family lives blocks from Toronto’s Greek Town, a lively and wonderful stretch of downtown populated by Greek restaurants and other family-owned businesses. It is completely inappropriate, inaccurate and corrosive to give our children the impression that the Greek people are somehow against the Jews by setting up modern-day showdowns.

Finally, the game of dreidel has taken on prominence in our contemporary packaging of Hanukkah in a way that has become problematic. While dreidel is a fun, holiday pastime, a clever little mnemonic device to remind children about the miracle of Hanukkah, it is nothing more than a game that has become elevated to the status of Jewish tradition along with its close compatriot, gelt (Yiddish for “money”). This has led to the unintended but highly unfortunate side effect of creating the appearance that money is central to our holiday, generating a market for edible coins and the like such as Hanukkah gift cards that contain images of golden coins alongside Hannukiot, dreidel and sufganiyot. Many Jews are outraged by collectibles found across Poland of Jewish figurines clasping a coin, yet they buy chocolate gelt by the pound as though it were central to Jewish continuity. Do we expect more thoughtful reflection on the perpetuation of age-old anti-Semitic tropes from gentiles than we do from ourselves? During a recent exchange with parents on how to talk about the holiday in their children’s public school class, this idiosyncrasy really hit home for me. By bolstering dreidel as essential, we risk giving the impression that gambling and hoarding shiny coins is germane to being Jewish.

While I have no doubt that there are thoughtful teachers and mindful parents emphasizing universal themes more relevant to the 2017 family, these products and programs indicate that Hanukkah has not yet shed its outmoded storyline. We’re long overdue to shape lessons about the Festival of Lights that make sense for today’s children growing up in a multicultural society that values gender equality, non-violent conflict resolution and bridge-building among ethnic groups. I am in favor of telling our children a big picture version of the Hanukkah story that speaks to the insistence of the Jewish people in maintaining their traditions and beliefs despite very strong outside pressures from the dominant culture. The message becomes ever more pertinent with the rampant “Chrismafication” of Hanukkah and also leads into talking to our kids about the importance of valuing and respecting different cultural practices from our own. While careful to steer clear of the binary of light versus dark and of stigmatizing darkness, I think the imagery of light lends itself to meaningful conversations (and art projects) about magnifying hope and drawing attention to important social justice issues. Rather than teaching the dreidyl game in your child’s classroom, try sharing a song that paints a picture of the love and freilechkeyt (joyousness) that have become associated with the festival. Its time to say goodbye to the tinfoil covered cardboard swords of Hanukkahs past and to embrace a celebratory, joyous holiday that honors religious freedom and shines a light or two (or eight) on diversity.

“’Chrismafication” of Hanukkah”‘

and

the judamafication of christmas

would this be the judamafication of hanukker

“How does making art of ancient Jewish militiamen bolster their Jewish self-understanding?”

I take it that hers is a rhetorical question?

The last sentence of the article is, “Its time to say goodbye to the tinfoil covered cardboard swords of Hanukkahs past and to embrace a celebratory, joyous holiday that honors religious freedom and shines a light or two (or eight) on diversity.”

But, I’m wondering how Jews can celebrate and honor religious freedom when Hanukkah is about conquering and coercing those who didn’t agree with your religion to either agree or be killed.

As usual, the Jewish double mind is at work. Jews seem incapable of ever truly meaning anything they say (or write) because their thoughts are so double minded. There appears to be an innate aversion to truth at work. Is it “built in” from the time of the “fall from grace”?