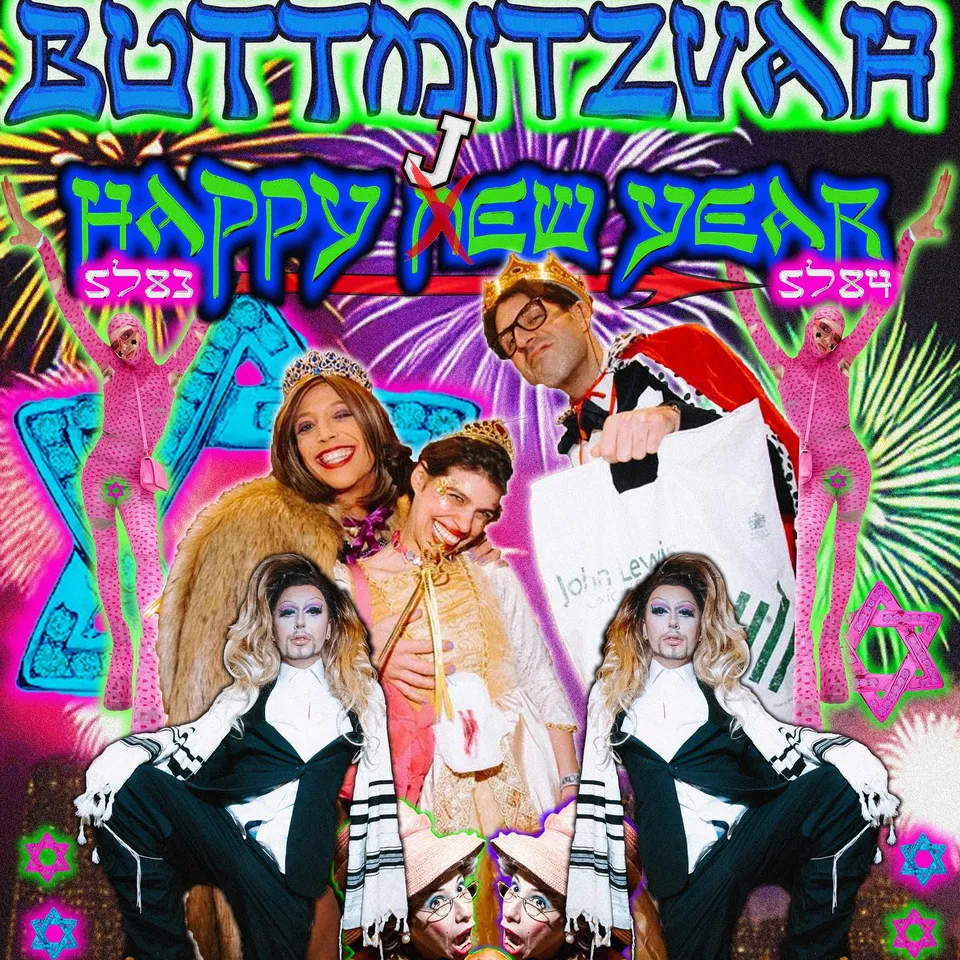

U.K. club night Buttmitzvah was created for those who feel too gay in Jewish spaces, yet too Jewish in gay spaces. Now in its seventh year, the inappropriate and campy ever-growing event is the perfect antidote to shame

ed note–but remember, the historical aversion on the part of Gentiles to Jews and to their perverse beliefs and behaviors has nothing to do with the perverse beliefs and behaviors of the Jews, but rather is all due to…

‘anti-Semitism…’

Haaretz

LONDON – Buttmitzvah is not your average bubbe’s night out. It features hundreds of people clad in skimpy, camp costumes embellished with Jewish insignia, rhythmically grinding to Middle Eastern hits by the likes of Sarit Hadad, Gad Elbaz and Tarkan.

“I had lived in Israel for three years and was just moving to London, and I was nervous about maintaining a meaningful connection to a queer-Jewish community,” Schaan recounts. “Before I moved, my friend told me about this queer Jewish party. It was on my radar as soon as I moved, and the first one was the Buttmitzvah Chrismukkah party.

Founder Josh Cole says Buttmitzvah was created in order to solve the problem of feeling too gay in Jewish spaces, yet too Jewish in gay spaces. “I think that all queer Jews can relate to a sense of isolation when they were younger, and that can potentially continue into adult age – and those feelings can be especially strong around bar or bat mitzvah age [12 for girls; 13 for boys],” he says. “Buttmitzvah is an attempt to reverse that and welcome everyone regardless of gender, age, race or sexuality, or religion to one big party.”

Each Buttmitzvah features the same recurring characters, including the Rimmers – a loving pastiche of a stereotypical North London Jewish family. Husband Merv and drag queen wife Gaye, proud owners of a luxury porta-potty business, are parents to obnoxious, hypersexualised bat mitzvah girl Becky, whose inappropriate outbursts provide the inspiration for the raunchiest dance numbers.

Every event has a different premise or theme, tailored to an upcoming Jewish holiday or Rimmer family affair.

Your correspondent had been planning to visit Schaan in London, and it was now obvious that the long-awaited trip needed to coincide with one of the biannual or triannual Buttmitzvah parties. I booked a flight and bought a ticket to Buttmitzvah’s Rosh Hashanah party on September 9.

Wednesday is rehearsal day, where Schaan has to teach the Buttmitzvah backup dancers the choreography he has devised for the Rimmer family songs. This time, Becky Rimmer will be singing “Kedem, Kedem,” named for the infamous grape juice served at Jewish holidays and events – a parody of Kylie Minogue’s Pride hit “Padam Padam.” The second song is “I Kissed a Goy,” inspired by Katy Perry’s “I Kissed a Girl.”

After meeting Schaan on the London Underground, we hurry to the Hackney rehearsal space, where I meet some of my fellow backup dancers for the first time. The dance moves do not come from the West End: For ‘I Kissed a Goy,’ we have to imitate fellatio and then vomit to the lyrics “It’s not what I’m used to, you’ve got all your foreskin on.”

Although none of us are professional dancers, three hours of rehearsals run by Schaan result in a semi-coherent series of movements. We film ourselves for at-home practice.

Cole joins at the end of the rehearsal, where he notes our additional duties for the New Year’s Eve party. These include greeting guests and handing out bagels and apples drizzled with honey, leading a hora, as well as dancing on stage to sustain the party spirit. Additionally, we are to dance to the traditional New Year song “Auld Lang Syne,” aptly renamed “Auld Lang Stein.”

The dancers are diverse in age and demography, yet all share a strong connection to their Jewish and queer identities.

Take 55-year-old David Rosenberg, for example, who first came to Buttmitzvah in 2022. London-born, formerly ultra-Orthodox and married to a woman, Rosenberg is playing Buttmitzvah’s resident drag rabbi, Rabbi Rosebud.

Now out and in a relationship for 23 years, Rosenberg says he has never felt so comfortable in a cultural setting. He cites Buttmitzvah’s inclusivity, which he says is multicultural rather than exclusively Jewish. “But within that, there’s total license for expression of Jewish culture in whatever way works for the individual,” he notes.

Now an official member of the Buttmitzvah family, I need to dress the part. As family members and greeters, a camp, warm welcome sets the tone for all Buttmitzvah guests.

I race around London’s many vintage stores to find the perfect NYE outfit. I settle on an ensemble comprising a black velvet and leopard-print jumpsuit, and am greeted in the mirror by 70-year-old Tutit from Bat Yam – on her morning walk dripping in ostentatious jewels, hands adorned with long red nails, replete with visor and fanny pack.

I complete the look with reflective shades and a blingy, oversize Star of David purchased in an East London market. Tutit is ready to rumble.

No Buttmitzvah is complete without bagels, so Schaan and I drive with co-founder Matthew Waksman to pick up 600 fresh bagels from a Jewish bakery in Brick Lane.

London is in the middle of a heat wave, so we work up quite the schvitz as we schlepp the hefty bags of bagels from the bakery to the car. As a pre-party snack, we sit in the car and gorge on smoked salmon and herring bagels, the air heavy with the delicious fishy-doughy steam. I’ve never felt more Jewish.

We then drive to Troxy, where the venue’s production team is already at work, preparing the stage with lighting, pyrotechnics and sound systems for the different acts that will perform this evening. The family members get busy cutting apples and putting the bagels into huge boxes covered in aluminum that read ‘MAZAL TOV’ in shiny blue letters.

After a quick dance rehearsal, we run to the dressing rooms to get into our costumes, some of which are seriously enviable. My favorites include the trio of naughty apples, and a sultry, burlesque interpretation of a beekeeper.

The Buttmitzvah family members have assembled for the family photo and a final run-through for the evening.

Other than our dances with them, the Rimmers also have their own comedy sketches, an opening act with famed British TV personality Vanessa Feltz (or Aunty Vanessa), a performance by drag queen and family member Ash Kenazi, and the New Year countdown.

The partygoers are no less diverse in age, gender and Jewishness. Some come dressed in 1980s NYE cupcake dresses (as per the Buttmitzvah NYE dress code), while others are hardly dressed at all, scantily clad with tiny mesh and sequin crop tops and shorts. Some wear kippot and others Chai or Star of David necklaces.

We kick off the party by introducing the family on stage, after which Aunty Vanessa leads the singing of “Dip the Schmekel in the Honey” – a naughty parody of the children’s holiday tune. We perform our dances with ruach (enthusiasm) and at about 1 A.M., are relieved of our duties and are able to party among the crowd.

The DJ plays a mix of mainstream party songs and Jewish summer camp anthems. This is the moment I am struck by some kind of stirring emotion: I have never experienced a Jewish simcha of this scale and type before, where queers, queer Jews, straight Jews, Israelis, goys and everyone in between dances together.

Growing up in Australia, being Jewish meant you were either part of an insular, close-knit Jewish community that had little interaction with “other” Australians, or you lived in a less populous community where you constantly felt like an ambassador of Judaism and Israel, repeatedly explaining our often odd traditions and practices. I was part of the latter group.

As with so many from minority backgrounds, I suppose at some point I began to associate my differentness as a source of shame, wherein the Jewish joy I felt in Jewish spaces was best segregated from the rest of my life. Buttmitzvah felt like an antidote to that shame: With its panache, glitz and glamour, it proves there is a place for Jewish pride and traditions in modern society.

I am not the only one who had realizations about identity and belonging. A queer Jewish friend of Schaan, Ed Berman, shared his thoughts after the event, echoing similar feelings.

“I haven’t heard that music and danced in horas since childhood simchas, and I now realize more how I was dealing with a lot of shame and self-denial at that time, so it felt really empowering to dance again in such a warm and belonging space,” Berman wrote to Schaan in a WhatsApp message. “I never expected to have that reaction.”

It is hard not to notice the overlapping struggles facing Jewish and queer pride. Being openly Jewish hasn’t always been safe nor accepted by the wider population in Britain. Antisemitism reached a record high last year, according to the Community Security Trust, with incidents spiking around security conflicts involving Israel and the Palestinians.

Though fundamentally different, members of the queer community face ostracization, violence and rejection by the wider society. Homosexuality was only legalized here in 1967, and legislation granting the queer community equality in adoption, civil union and other areas of family law was only passed in the last 20 years. Yet discrimination is still pervasive. One in five members of Britain’s LGBTQ community experienced violence or an incident linked to their sexuality according to a 2017 report.

“There’s a lot of heaviness in the Jewish community and antisemitism has become rather popular again,” says Cole. “Buttmitzvah provides a space for people who don’t have such an obvious place in the Jewish community, as well as a large non-Jewish contingent.

“Buttmitzvah is a radical expression of Jewishness in the public sphere,” he adds. “There’s never been Jewishness celebrated in British society like this outside of film and TV. It does a lot for contemporary Jewish culture – creating a space that Jews and non-Jews very much feel a part of.”

They say that exposure is the antidote to fear. Witnessing thousands of people dancing to the Yiddish and Hebrew songs that were played at bar/bat mitzvahs, weddings and summer camp – the same songs that make us the ‘other’ in the wider community – I felt relief and joy simultaneously.

The dancefloor thins and the partygoers head for their next destination. I don’t want to leave, but we drift out into the cold London street. Just like Schaan felt after his first Buttmitzvah, I feel struck by disbelief after dancing my tuchus off on stage for over 3,000 people. The openness, kindness, progressiveness and chutzpah of the Buttmitzvah experience has truly moved me in a way I never expected.