His opposition to the US-led Madrid peace process as deputy foreign minister made him persona non grata at the State Department

ed note–in light of what is going on now and what has been taking place ever since a certain real estate developer from NY named Donald J. Trump announced his intention to seek the Presidency, pieces such as this are of VITAL IMPORTANCE in understanding the political machinations taking place on the part of organized Jewish interests in trying to undo Trump’s plans for ‘peace’ in the Middle East, and, just as importantly, the fact that the same primary characters–Netanyahu–who moved against another president using his office to advance a ‘peace deal’–George H.W. Bush–are involved as well.

Times of Israel

When a president dies, the tendency is to put aside long-simmering resentments and consider the wholeness of his record.

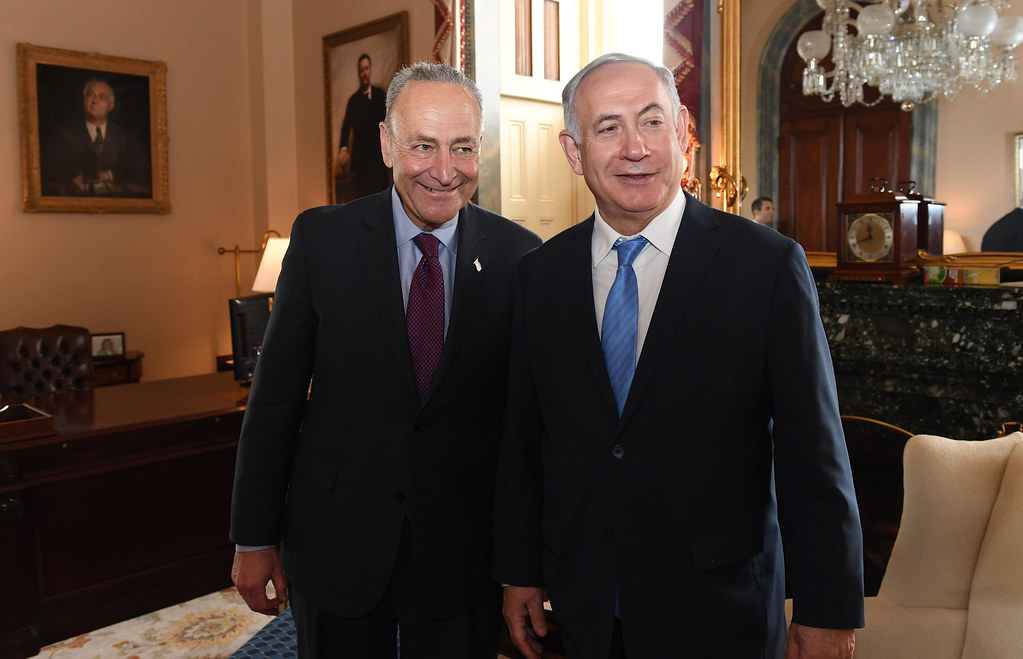

So it was when Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu remembered George Herbert Walker Bush, who died last week at 94.

Despite the tense relationship with Israel that was a hallmark of Bush’s single term, the prime minister praised the late president for things that a younger Netanyahu fiercely opposed.

‘We in Israel will always remember his commitment to Israel’s security, his decisive victory over Saddam Hussein, his important contribution to the liberation of Soviet Jewry, his support for the rescue of Ethiopian Jewry, as well as his efforts to advance peace in the Middle East at the Madrid Peace Conference,’ Netanyahu said at the launch of Sunday’s Cabinet meeting.

In real time however, Netanyahu, a deputy foreign minister during much of Bush’s 1989-93 term, had a real problem with two of the Bush agenda items he now praises-

1. How Bush handled the first Gulf War,

and–

2. The demands he put on Israel at the Madrid Peace Conference.

Netanyahu’s opposition to the Madrid process made him persona non grata at the State Department.

Still, his praise for the process this week is not so much a matter of polite hypocrisy but a signal of how he has evolved: The principles underpinning Madrid now inform Netanyahu’s approach to peacemaking.

Netanyahu was the most outspoken member of Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir’s government opposing the request from the Bush administration not to retaliate should Saddam Hussein provoke Israel after Bush pledged to drive Saddam out of Kuwait. Netanyahu said it was a “certainty” that Israel would retaliate.

After US forces launched their war to oust Saddam and the Iraqi dictator launched missiles at Tel Aviv, Shamir decided to heed Bush and the US president later thanked him for his restraint. Netanyahu was vindicated somewhat when Israeli military analysts came to believe that reticence to retaliate during the Gulf War emboldened Hezbollah to strike Israeli targets in subsequent years.

Bush also leveraged the US victory over Saddam in getting Shamir to send a delegation to the Madrid talks. Shamir hated the idea of the talks, so much so that he sidelined his actual foreign minister, David Levy, who was open to the talks, and instead made a star of Netanyahu, who was relentless in his criticism of not just the talks but of their land-for-peace premise.

Bush’s Secretary of State, James Baker, was so frustrated with what he perceived to be Netanyahu’s obstructionism that he banned him from the State Department.

The Madrid talks led to the Oslo process, which launched direct Israeli-Palestinian negotiations.

Netanyahu built much of his subsequent career on saying that Oslo was a mistake because it promised the transfer of critical territory to an entity that Israel could not trust to secure it.

It’s an outlook that has helped get Netanyahu elected four times as prime minister.

Instead, in recent years he has favored a multilateral peace that includes all major Arab players in the region. He relies on Saudi Arabia to bring others into the process and builds towards a ‘final status’ plan through regional cooperation. Key to Netanyahu’s approach is that the Palestinians do not have the power to prevent other Israeli-Arab talks from advancing.

If that sounds familiar, it should: Bush 41 suggested something similar in a familiar context.

‘What we envision is a process of direct negotiations proceeding along two tracks — one between Israel and the Arab states, the other between Israel and the Palestinians,” Bush said at the opening of the Madrid peace parley on Oct. 30, 1991. “This conference cannot impose a settlement on the participants or veto agreements.’